Now Available as an Audible Audiobook

Posted: March 17, 2023 Filed under: Caregiving Books, Topics of Current Interest 1 CommentWhat to Do about Mama? Expectations and Realities of Caregiving

By Barbara G. Matthews and Barbara Trainin Blank

Featuring :Ann Flandemeyer and Murren Kennedy

Available NOW on Amazon as an Audible Audiobook

Visit my Author Page on Amazon Central

https://www.amazon.com/author/barbaramatthews

Podcast: PositiveAging Sourcebook

Posted: July 27, 2021 Filed under: Topics of Current Interest Leave a commentTo listen to the podcast, click on the the following link:

Podcast: The Caregivers Corner

Posted: July 1, 2020 Filed under: Topics of Current Interest | Tags: Caregivers Corner Podcast, Matt Gallardo, Messiah Lifeways, What to Do about Mama? Podcast Leave a comment

Click above to listen to Episode 30 of the Caregivers Corner: What to do About Mama?” Expectations & Realities of Caregiving. I really enjoyed the opportunity to talk with Matt Gallardo, Senior Director of Community Engagement at Messiah Lifeways.

The Caregivers Corner

(Formerly knows as The Coach’s Corner)

Matt Gallardo: “In Episode 30 we talk about the book “What to do About Mama?” Expectations & Realities of Caregiving with co-author Barb Matthews. She along with Barbara Trainin Blank open their hearts and bear their souls to share their challenging, heart wrenching, and insightful journeys as caregivers. Their personal stories, along with a host of other caregiving contributors, give detailed perspective on this physical, mental, and emotional roller coaster that caregiving entails.” To purchase a copy:

- Sunbury Press (publisher): www.sunburypressstore.com/What-to-Do-A…ategoryId=-1

- Amazon: www.amazon.com/dp/1620061988/

Thanks Matt! I enjoyed our conversation and hope your listener’s will too.

Moratorium

Posted: December 30, 2021 Filed under: Miscellaneous, Topics of Current Interest | Tags: Time Out, What to Do about Mama? moratorium Leave a comment

In 2013 the first edition of What to Do about Mama? was published by Sunbury Press. My idea to write a book about caregiving was initiated by my experience as a caregiver for my mother-in-law. After my caregiving role ended, I remember thinking, “I could write a book!” I think many of us have a thought like that one time or another. But in this case, I did—along with my co-author and some three dozen other caregivers. In all honesty, my thought was that others might benefit from the real-life information we had to share.

And maybe it has. My daughter-in-law was pleased to tell me that her aunt is reading the book (the second edition published in 2019), “loves it,” and “wishes she had read it before she was a caregiver.” That is a typical response to caregiving books. Why? Because most people avoid thinking or talking about caregiving as a means of denying the day will come. I will think about it “when I need it” becomes “dealing with it in the crisis moment.”

This is a topic I have addressed—a lot—along with some other What to Do about Mama? ‘s main themes, such as family relationships and shared responsibility; the emotional impact of caregiving; and avoiding the burden of caregiving by planning and preparing ahead. (Check out the Index of Blog Posts on the menu bar.)

Caregiving had a profound influence on my life. It impacted my health, my relationships, and my outlook on the future. If you subdivide the population into young, middle-aged, and old, my peers—family, friends, neighbors, and acquaintances—fall into the latter group, whether admitted or not. Sure, there are many subgroups based on attitudes and physical condition, but still, we fall into the category of “old.”

- I say this because reports of illness and death are more frequent.

- I say this because I know that no matter how much effort we make to stay young, fit, and sound, we cannot change the inevitable.

- I say this because of the number of times I look at my peers and feel the urge to shout, “Watch out!” as if they are ready to step in front of an oncoming unseen car. Even those who are health care professionals and social workers. Because avoidance and denial are common to all of us.

By now you may be wondering why I have chosen to write about this topic. It is because I want to tell you that I am initiating a moratorium from this What to Do about Mama? WordPress blog, as well as the on the monthly What to Do about Mama? newsletter.

My husband, who worked in the steel industry for 48 years, retired in September. Although I love to write, it is, for me, a painstakingly slow process keeping me at the computer for many hours. That was fine when he was working, and even better during COVID’s pre-vaccination days. But now, I need to free myself from the tether. I’m leaving my options open so that I will have the ability to communicate via these channels again when so moved to do so. But it certainly won’t be on a regular basis.

There are still a couple of initiatives in the works. One is a What to Do about Mama? audiobook. The other is a collaborative book project I have been working on for the past five years with a former student. Although it was initially accepted for publishing, there are legal ramifications that need to be worked out that put that eventuality into question. Although not a book about caregiving, I will let my followers know if the project comes to fruition.

Barb Matthews

Family Relationships: Sharing Caregiving Responsibilities

Posted: December 3, 2021 Filed under: Impact on Family Relationships | Tags: Area Agency on Aging, expectations, Family Caregiving, Giving back, Pamela Wilson, shared responsibility, The Caring Generation Leave a comment

Caregiving as a shared responsibility is a main theme of my book, What to Do about Mama? It is also the theme of Pamela Wilson’s Caring Generation November 24, 2021, podcast: Why Won’t My Family Help Me – The Caring Generation® by Pamela Wilson

Why Won’t My Family Help Me – The Caring Generation® (pameladwilson.com)

As is my general pattern, I will share those features of my caregiving experience that relate to Pamela podcast by using excerpts from What to Do about Mama?

I met my husband in 1966 on our first day at college. The first thing I learned about him was that he came from a military family and that his dad, mom, brother, and two sisters were all still living in Germany.

I met David’s family the following summer when they returned to the States, and I was thrilled to be included in their family life. My own family had sort of disintegrated after my father passed away a few years earlier. I always felt cared for and included by David’s family, and that did not change after we married.

What to Do about Mama? p. 7

From the beginning, I considered my husband’s family to be my family—like I was a daughter and a sister rather than a daughter-in-law or sister-in-law. I experienced the family’s “life events” from that perspective, too.

In 1994, my father-in-law passed away suddenly in his sleep one night. He died in a way that many of us would “like to go.” Later, my mother-in-law told me she was not only surprised when she awoke to find him still in bed at eight o’clock in the morning, but she was shocked when she nudged him and he did not respond. This expression of emotion was more than she generally displayed. My in-laws lived in Florida, where they had moved in 1971. It was unusual for them to live in one place for so long, since Dad had been in the military for thirty years. Mom did not drive, and David and I extended an open invitation for her to live in our hometown.

What to Do about Mama? p. 8

The time came when the family felt that Mom was no longer safe living alone in Florida, it was just a matter of course that she would live near us.

The general consensus was that if Mom would agree to the move, our hometown was probably the best choice because of the proximity of family members. In addition to David and me, our three grown children lived in the area, as well as one of Shelley’s sons. Shelley and Sandy each lived about two hours away, and it was expected that Scott could fly in easily. We anticipated that they would all make frequent visits.

What to Do about Mama? p. 9

After a couple of years, my mother-in-law’s health began to decline significantly. At the time, I was working as an Assessor at the Area Agency on Aging. My job impacted my attitude about caregiving in a number of ways. First of all, I felt that my career experience had uniquely qualified me to be a caregiver. Secondly, I was influenced by many of the caregivers I had observed on my job.

*Families that had attached in-law quarters—close but separate—appeared to me to fare better. *Caregivers demonstrate love and appreciation through the sacrifices that they make. I was moved to tears by a gentleman who had “retired” early to care for his mother with advanced dementia. He told me, “Miss Barb, my mother does not know who I am. But at night, when we sit on the couch watching TV with my arm around her and her head on my shoulder, it is all worthwhile.”

What to Do about Mama? p. 39

I was gratified to be able to “give back” to a family that had given so much to me.

I had the opportunity to demonstrate to my mother-inlaw and siblings-in-law my appreciation for being a part of their family since I was eighteen years old. I was also able to show thanks to my parents-in-law for providing support in our times of need. Most of all, I was able to show gratitude for their assistance and encouragement in helping to provide our children with their college educations. This was to be my gift to my all of my in-laws.

What to Do about Mama? p. 35

So, my mother-in-law moved in with us and I quit my job to be her fulltime caregiver. The arrangement lasted for four years—the first two were good—the last two were not. It had been my expectation that my husband’s family would pull together like another family I had the pleasure of observing.

*I remember one snowy day driving down a gravel driveway to an old family homestead and being surprised that all five children took the time to come to the assessment for their mother to receive services.

What to Do about Mama? p. 223

*One thing that becomes very clear from our reading of the caregiver responses and the stories in this book is that caregiving has a profound impact on family relationships. If your family unit has always been strong and you all pull together to meet this challenge, your relationship will probably grow even stronger from sharing responsibilities and supporting one another through the experience.

But ultimately, this was not the outcome of our caregiving arrangement.

Despite a good multi-decade relationship, the difference in our family cultures and its impact on who we were as people was just too vast. Once the trouble began, interaction among all parties became increasingly difficult, and then impossible. That was the quicksand I never saw in my path.

What to Do about Mama? p. 40

Click on the following link to listen to Pamela Wilson’s Podcast about the five reasons why families won’t help. Why Won’t My Family Help Me – The Caring Generation® (pameladwilson.com)

Five reasons why family won’t help:

- If your family members are not caregivers, they may not understand what you do all day.

Understanding the responsibilities of any job—caregiving included—requires an understanding of the job responsibilities. It involves experiences hands-on practical tasks under the type of emotional stress many caregivers experience. Everyone involved needs to learn that there is a big a difference between help that helps and help that creates more work for you. Oftentimes family members who are not caregivers stand on the sidelines giving advice or directing the caregiver what to do, which is generally not appreciated. Good caregiver communication is the key to overcoming these challenges, but there are no guarantees that all parties will be proficient at communicating. - Dealing With Critical Family Members.

Family members can be judgmental and refuse to help when you don’t do things “their” way, which they consider to be the “right” way. They may then choose not to be involved. To cope with your critics, try not to take the criticism personally with the understanding that that there is usually a deeper reason for their response that has nothing to do with you. (For example, guilt at not stepping up like you.) Choose how you respond be aware that there is the potential for this negative event to be an unforeseen positive. - Differing belief systems.

Changing beliefs is as difficult as changing habits. Some families believe that family takes care of family regardless of the situation, others do not. Even withing the same family, there are factors from childhood that have an impact you don’t know about. (Sibling rivalry is a good example that comes to mind.) - Family interactions with caregiver.

What is your history? Have you let others down? Broken commitments? Been unreliable or untrustworthy? Hard feelings can be harbored for years. The intentions of caregiving siblings may be met with suspicion. Both past parent-child relationships and sibling relationships impact the type of care aging parents receive, and current belief systems have influence as well. Family beliefs can conflict with the family working as a team. It is most common that one caregiver bears most of the responsibility for an aging parent. - Family May Not Help Due to Life Situations or Timing

Different siblings may be in different life stages. You may need to give the wake-up call you can no longer be the caregiver before other siblings to step up. Since you’ve been managing point your sibling may hesitate to upset the status quo. If that’s the case, it’s up to you not to let a lack of family support place your life on hold. (Be prepared for your relationship to be permanently changed.)

Surviving the Unimaginable: How to Cope with the Death of a Spouse

Posted: November 22, 2021 Filed under: Topics of Current Interest | Tags: death of spouse, grief, info@elderfreedom.net, Michael Longsdon Leave a comment

Guest Post by Michael Longsdon info@elderfreedom.net

The death of your beloved spouse can shatter your entire world. There will be undeniable grief and sorrow as you mourn the love of your life. You might even begin to wonder how you’ll go on without them. For seniors who have possibly shared so many decades of their life with their significant other, it can be particularly difficult to move forward.

It’s important to realize that you are not alone. An estimated 800,000 people are widowed each year in the United States alone. Regardless of what some well-meaning people might tell you, there is not a “right” or “wrong” way to deal with the death of your beloved spouse. There is no specific amount of time you “should” take to grieve. The process is different for everyone.

Luckily, there are some time-tested words of wisdom that can help you cope in the weeks, months and years that follow the loss of your loved one:

First and foremost, give yourself time to grieve. During this process, you will undoubtedly need some support. Even for those with a solid support system and strong resilience, there is an unbelievable amount of grief that occurs when we lose our lifelong partner.

There will be some immediate needs that you will need to take care of, such as funeral planning and managing your household’s finances. It is common to feel overwhelmed by these sudden tasks – especially if your spouse typically handled most of the finances. Again, give yourself permission to reach out for help if you need it. Chances are, there might be a loving family member or a trusted friend who is willing to take on a few extra responsibilities to support you in this process.

Many people decide to move after the death of a spouse. This should not be a decision that is taken lightly, but instead should be made only after you’ve taken some time to really consider what is best for you. If you do eventually decide to move, you will want to properly handle and preserve any family heirlooms as items are either packed away into storage or donated. Not only do you want to protect the item, you also don’t want anything to get damaged in the process.

Regardless of whether or not you decide to move, you might also want to consider turning one of your beloved heirlooms into a memento. Choose an item that has special meaning to both yourself and your spouse, possibly something that reminds you of a happy memory or a certain aspect of his or her personality. Consider keeping the item and turning it into a keepsake that you can cherish for years to come.

As you work through your grief, you may look for other significant ways to remember your spouse. One excellent way to memorialize your loved one while also helping others is to start a nonprofit. As doing so can be complicated for those who aren’t familiar with the process, ZenBusiness offers step-by-step guidance on how to form your nonprofit. Especially if your loved one passed as a result of a specific medical condition or if there was a cause they were particularly involved in during their lifetime, a nonprofit can be a great way to raise awareness and funds while helping others in the process.

You don’t ever really get over the death of a spouse. But with patience and time, you will eventually get through it. Although the person you loved might be gone from this world in a physical form, they will always live on in your heart – and in your memories of your good times together.

Burnout Blues

Posted: November 10, 2021 Filed under: Emotional and Physical Challenges, Impact on Family Relationships, Miscellaneous | Tags: burnout, Jenn and Joji Podcast, NO, self-care, self-talk, signals of burnout, super antibodies Leave a comment

Have you ever sat in a coffee shop and “overheard” a neighboring conversation? If that is something you like to do, but feel guilty about eavesdropping, tune into the Jen and Joji Podcast.

Jenn and Joji Podcast

https://www.spreaker.com/user/15265580/episode-4-burnout

Here you will hear the chitchat of two (Millenial?) friends as they share their thoughts about a wide variety of topics, such as perfectionism and sobriety. The podcast I chose was BURNOUT, and although they largely spoke in general life terms, the conversation touched on and applied to the specific topic of CAREGIVING.

Jenn is an elementary school teacher whose entire nuclear family–both the spouses and their two young children–are overcoming a bout with coronavirus. Jenn noted that they now have SUPER ANTIBODIES. Jenn expressed that their COVID experience was like a “mini 2020” because of their return to quarantine status.

Joji is a nurse who had just experienced an overwhelming week, which consisted of work (an unusual 5-day shift) in conjunction with a week of caregiving (a responsibility she and her siblings share on a rotating basis). By Friday she felt like she was hitting a wall, noting that it felt like a train was barreling down on her that could not be stopped.

Respite care helps caregivers avoid burnout by taking time away from the senior-care environment. It helps prevent the depression that develops when caregivers do not make time for a well-rounded personal life. Again, respite care falls within the realm of family responsibilities and provides another good opportunity for friends or volunteers to help. But if these resources are not available to you, paid services are accessible in-home through independent caregivers and home-health agencies, or out-of-home at assisted-living or nursing-home facilities, adult day centers, and family respite-care homes.

What to Do about Mama? p. 184

These experiences led Jenn and Joji to talk about burnout and how to cope. They touched upon the following:

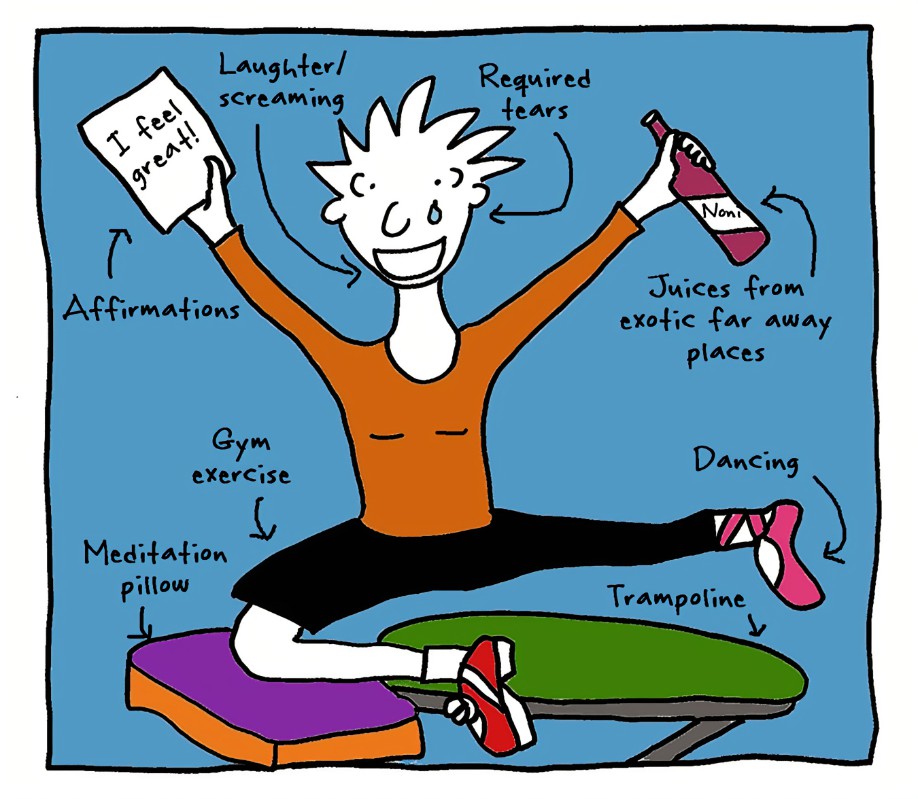

Signals of burnout:

- Losing patience and being bothered by the “little things”.

- Turning to alcohol, rationalizing that you “deserve” it, then feeling worse afterwards.

Self care as a ways to deal with burnout:

- Use positive self-talk that does not assign an emotion to your feelings.

- Acknowledging that you are burned out and taking time to “pause”

- Learning to let go and not expecting yourself to be “perfect”

- Establishing basic healthy habits (such as eating right, exercising and getting enough sleep)

Relationships and asking for help:

- AT HOME

From your spouse and children (it’s a good way for them to learn independence)

From your siblings (as in sharing the responsibilities of caregiving) - AT WORK

From your Boss and Co-workers.

Remember you are a TEAM

Most importantly:

“I learned how to say, ‘NO,’ in addition to knowing when to say, ‘Yes.’”

What to Do about Mama? p. 267

Confessions of a Caregiver

Posted: October 20, 2021 Filed under: Emotional and Physical Challenges, Impact on Family Relationships | Tags: caregiver emotions, caregiving education, elder care, experience gap, Pamela Wilson, The Caring Generation 3 Comments

Caregivers—do you sometimes think horrible thoughts that you are uncomfortable sharing with others (except maybe with an online support group)? Or maybe you have simply blurted out something terribly inappropriate and then thought, “I can’t believe I said that!

Well, I have. (More on that in a minute.)

That is the topic of Pamela Wilson’s September 15, 2021, podcast “Wishing a Sick Parent Would Die

If you are not a caregiver you might be shocked if you were to hear a caregiver say they wish a parent would die. You might wonder how someone could possibly feel or think this way to the point that they could utter such words.

It’s easy to be judgmental, and challenging to be empathetic—especially when you don’t fully understand the daily life of caregivers. THE OTHERS–they just don’t get it. Because of what is called experience gap there is a lack personal insight when you are not experiencing caregiving on a full-time basis.

So, click on the link below to listen to the Caregiving Generation podcast. You will gain broader understanding and new perspectives whether you are a Caregiver or a family member who may not “get it” and are therefore, in need of education.

Wishing a Sick Parent Would Die – The Caring Generation® (pameladwilson.com)

My less-than-stellar Caregiver Comment Confession:

“I have no desire to touch your mother in that way, and at times

I can hardly even stand to see, smell, or hear her around me.”

During the family meeting Sandy had said that seniors become more childlike, more egocentric. She expressed strongly that Mom would benefit from being touched. She expected hand-holding and hugging and suggested that I do that more. I could see that my very frank and harsh reply shocked her. “I have no desire to touch your mother in that way, and at times I can hardly even stand to see, smell, or hear her around me.” I couldn’t believe the sound of my own words, which were much worse than their actual meaning—that there was no getting away from Mom’s presence, even when she was visiting someone else. I think those words finally got through to Sandy—that the emotional turmoil we had been through the past year had reached the point that it was imperative to find a resolution to the growing problems. I moved on from being disappointed and angry; I was now distraught.

What to Do about Mama? pp. 17-18

Caregiving: Facing the facts

Posted: September 28, 2021 Filed under: Assuming Caregiving Responsibilities, Emotional and Physical Challenges, Financial Considerations, Impact on Family Relationships | Tags: caregiving plans, eldercare, family cultures, Pamela Wilson, The Conversation Project Starter Kit Leave a comment

As I began to glance at Pamela Wilson’s Sep 22, 2021 Podcast: Hard Truths About Caring for Aging Parents – The Caring Generation® the hard truths started jumping out at me right and left. I had learned about many of those hard truths the hard way—by first-hand experience

Hard Truths About Caring for Aging Parents – The Caring Generation® (pameladwilson.com)

In this blog post, I will identify some of those hard truths and then share how they impacted my own caregiving experience and how I anticipate they will impact me and my family in the future.

- Decide how much interaction you want with your parents throughout your life. The decision to remain living in the same town as your parents or move away affects caregiving responsibilities later in life.

This decision is not always yours to make. Both my mother and my husband’s parents chose to move away from us when they retired to Florida. My mother and my father-in-law both died suddenly; there caregiving needs were never very great. My mother-in-law, however, had a goal of living to 100 and did her best to accomplish that goal, despite having a number of serious health conditions. When she became unsafe living on her own, she moved closer to us. My son and two daughters were all married with families, but they always found time to be supportive of their grandmother. When her caregiving needs became much greater, she moved into our home with me as her primary caregiver. My children continued to be supportive. (My mother-in-law died just short of 90.).

Although my husband chose not to move away from our children, our older daughter and her spouse decided to relocate from our hometown when their kids were old enough that they no longer needed as much family support. Since then, she made it clear she does not intend to be a caregiver. Her younger sister thanked me for being such a good example when I cared for her grandmother. I certainly encourage the children to be supportive of each other when the time comes that we may need some help.

- Be aware that life cycle transitions affect the timing and care of aging parents. Few children expect to spend their retirement years caring for aging parents. Still, many retired adults become caregivers—if not for a spouse, then first for aging parents. Caregiving responsibilities often pass from one generation to the next. Although some families may believe in the responsibility to care for aging parents—is there another way to make sure parents receive care and you are not the only caregiver? There isn’t one right or wrong way, but one solution is for families to think about caregiving differently, from a whole-family perspective that take lifecycles into account: having and raising children, caring for aging parents, caring for a spouse, and caring for the caregiver.

- Family culture has a strong impact on how families handle the issue of caregiving. Is the family individualistic, believing in self-sufficiency or collectivist, setting aside individual achievement to work toward the good of all in the family? Does the family talk openly about the unpleasant realities of life and death? Some elderly parents may refuse to talk about legal planning or burial plans, whereas some adult children find talking about the death of a parent too emotionally traumatic. A family generally benefits if they can discuss sensitive topics openly as a recurring topic instead of a subject of hesitation and disagreement.

This was one of the biggest challenges when I was my mother-in-law’s caregiver. As one sister stated, “We never talked about anything. We just moved on.” When we came to the point that I was coming to a point of resentment because of their comfort with my assuming the role, which diminished their need for sacrifice, I forced the issue by insisting on a family meeting and requesting greater shared responsibility. Although that eventually led to more involvement, it also led to hard feelings that still exist ten years after my mother-in-law passed away. Setting boundary lines increased their participation and helped rid me of resentment, but I also think that it increased theirs—but there are times that difficult decisions must be made in order to avoid even greater consequences.

- Caregiving and care costs affect family income. It’s important to have conversations about the cost of caregiving ahead of time. Potential caregivers need to consider how it will impact their educations and careers. If you don’t talk about caregiving ahead of time, you will find yourself learning after you are embroiled in the role. Often families move in together to provide care for an aging parent with the thought of saving money. Too frequently, however, when a son or daughter gives up their job to be a caregiver, they become financially strapped. Sometimes caregiving appears to be an opportunity to escape from a job or a boss you hate.

Because I quit my job when my mother-in-law moved into our home, she paid the mortgage (equitable to the cost of her apartment in the independent senior living facility where she had been living) because that is what my salary had covered previously. She also named my husband as her life insurance beneficiary to compensate for the loss of social security and pension monies from my early retirement. Although my husband’s siblings had agreed to the arrangement ahead of time, it did not seem to settle well with them when the estate was settled.

- Caregivers often give up or trading parts of their lives to care for aging parents. Should you? For how long? The cost is great when you were the only person to step up.

Today, as I age and my health declines, I often feel that I squandered the last best years of my life as my mother-in-law’s caregiver. At those points my counterpart sister-in-law’s comment comes to mind: “My priority is my children. I am only a daughter-in-law.” What to Do about Mama? p. 20

- A lack of planning affects family relationships. When there is no planning because the topic of caring for aging parents is something no one wants to talk about, unpleasant and unwanted decisions are not avoided. Caregiving becomes a process of action and reaction that elicit a response only when serious concerns are manifested, or a crisis moment occurs. Ripple effects are then created that affect every generation in the family.

A few years ago, both my daughter-in-law and my son-in-law’ mothers were diagnosed with cancer. The first family spoke openly of the diagnosis. She opted not to undergo treatment and after five months, passed away.

“There was all this anticipation of need when the diagnosis came, but that need did not actually manifest itself much until the last few weeks of my mother’s life. She was fortunate to live comfortably until then, and was indeed in decent enough shape, that she was still making coffee for my dad every morning, up until those last few weeks. Our help for her was largely emotional support and keeping true to her wishes of spending as much time with family as she could. My mother waited until she’d checked the last items off her “To Do” list—a granddaughter’s birthday, a dance recital, and Dad’s hemorrhoid surgery—and then she stopped eating. She passed away on Father’s Day, surrounded by her husband and children who loved her so.” What to Do about Mama? P. 280

When I offered my son-in-law a copy of “The Conversation Project” which encourages dialogue between parents and children, he was angry with me, calling me “insensitive”. His mother opted for treatment, but sadly, the result was the same. Without going into the details, I think it would be accurate to say that her experience was in many ways, quite different that the one described above.

https://theconversationproject.org/

- It’s never too early to make a plan. Consider how caring for a parent will affect you, your marriage, your family, and your career. There are times when you must make difficult decisions in order to avoid even greater negative consequences.

I found from personal experience that Caregiving isn’t a short-term project. It can go on for a year, three, five, ten, twenty, or more. If you are proactive about making choices for on-going care you may avoid the caregiver burnout and frustration—the sources of emotional stress that can cause one’s health to decline. I know it did for me.

Proactive Caregiving

Posted: September 1, 2021 Filed under: Assuming Caregiving Responsibilities | Tags: Aging Parents, Cynthia Hickman, eldercare, life cycles, senior care Leave a commentCynthia Hickman gets right to the point in her August 16, 2021, blog post of “Your Proactive Caregiver Advocate: Dr. Cynthia Speaks!” and it’s a valuable point, to be sure.

Take the Blinders Off-Your Parents Are Aging!

Cynthia Hickman’s life-events regarding the death of her parents are similar to mine. Her father died in 1965 at the age of 46, whereas her mother did not pass away until 2017 when she reached a more advanced age. My father died in 1963 at the age of 48—and the circumstances of his death were a major formative factor in my life. My mother died in 1998 at the age of 77, which—although a more “acceptable” age—is one that heightens my own awareness of mortality, since I am now 72.

Cynthia Hickman talks about the circle of life and points out that the process of our bodies breaking down is nothing more than a natural part of life’s cycle. She goes on to ask the question:

Should We Prepare or Should We Wait?

It is her position that “we must remove the blinders and deal with the reality of our family circle.” She recommends that we acknowledge the actions and patterns of those we love; that we are proactive and self-aware of our roles, and that we embrace readiness rather than run from it.

I have had some major life experiences that form my perspective—and I must report that, like Cynthia, I have a strong belief in “prepare”. Although you can never be in “control” of everything that happens in life, by adopting Cynthia’s mode of thinking you will find yourself in a better position to step into caregiving with less stress and more confidence in your ability to handle life-challenges.

When you avoid confronting difficult topics—often to the point of denial—they only become more challenging because you are ill-prepared. Furthermore, you will create a greater burden for your own children when the time comes that you are in need of care.

Following is a list of my own past blog posts that deal the topic of being prepared.

- Attitudes about Caregiving Education

- The “We don’t need it yet” phenomenon

- Thoughts about Denial

- More about Denial

- Becoming a Caregiver and Planning for the Future

- Burdening Our Kids–Revisited

- Lickity Splickity or Little by Little?

- Downsizing

- It Pays to Prepare

- Processing the Pictures

- Belongings

- The Conversation Project